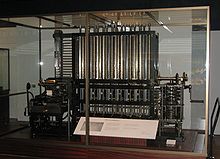

Charles Babbage, FRS (26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871)[1] was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who originated the concept of a programmable computer.[2] Considered a "father of the computer",[3] Babbage is credited with inventing the first mechanical computer that eventually led to more complex designs.[4] Parts of his uncompleted mechanisms are on display in the London Science Museum. In 1991, a perfectly functioning difference engine was constructed from Babbage's original plans. Built to tolerances achievable in the 19th century, the success of the finished engine indicated that Babbage's machine would have worked. Nine years later, the Science Museum completed the printer Babbage had designed for the difference engine.

Birth

Birth

Babbage's birthplace is disputed, but he was most likely born at 44 Crosby Row, Walworth Road, London, England. A blue plaque on the junction of Larcom Street and Walworth Road commemorates the event.[5]

His date of birth was given in his obituary in The Times as 26 December 1792. However after the obituary appeared, a nephew wrote to say that Charles Babbage was born one year earlier, in 1791. The parish register of St. Mary's Newington, London, shows that Babbage was baptised on 6 January 1792, supporting a birth year of 1791.[6][7][8]

Babbage's father, Benjamin Babbage, was a banking partner of the Praeds who owned the Bitton Estate in Teignmouth. His mother was Betsy Plumleigh Teape. In 1808, the Babbage family moved into the old Rowdens house in East Teignmouth, and Benjamin Babbage became a warden of the nearby St. Michael's Church.

Education

His father's money allowed Charles to receive instruction from several schools and tutors during the course of his elementary education. Around the age of eight he was sent to a country school in Alphington near Exeter to recover from a life-threatening fever. His parents ordered that his "brain was not to be taxed too much " and Babbage felt that "this great idleness may have led to some of my childish reasonings." For a short time he attended King Edward VI Grammar School in Totnes, South Devon, but his health forced him back to private tutors for a time.[10] He then joined a 30-student Holmwood academy, in Baker Street, Enfield, Middlesex under the Reverend Stephen Freeman. The academy had a well-stocked library that prompted Babbage's love of mathematics. He studied with two more private tutors after leaving the academy. Of the first, a clergyman near Cambridge, Babbage said, "I fear I did not derive from it all the advantages that I might have done."[citation needed] The second was an Oxford tutor from whom Babbage learned enough of the Classics to be accepted to Cambridge.

Babbage arrived at Trinity College, Cambridge in October 1810.[11] He had read extensively in Leibniz, Joseph Louis Lagrange, Thomas Simpson, and Lacroix and was seriously disappointed in the mathematical instruction available at Cambridge. In response, he, John Herschel,George Peacock, and several other friends formed the Analytical Society in 1812. Babbage, Herschel, and Peacock were also close friends with future judge and patron of science Edward Ryan. Babbage and Ryan married two sisters.[12] As a student, Babbage was also a member of other societies such as the Ghost Club, concerned with investigating supernatural phenomena, and the Extractors Club, dedicated to liberating its members from the madhouse, should any be committed to one.[13][14]

In 1812 Babbage transferred to Peterhouse, Cambridge.[11] He was the top mathematician at Peterhouse, but did not graduate with honours. He instead received an honorary degree without examination in 1814.

Design of computers

| “ | In 1812 he was sitting in his rooms in the Analytical Society looking at a table of logarithms, which he knew to be full of mistakes, when the idea occurred to him of computing all tabular functions by machinery. The French government had produced several tables by a new method. Three or four of their mathematicians decided how to compute the tables, half a dozen more broke down the operations into simple stages, and the work itself, which was restricted to addition and subtraction, was done by eighty computers who knew only these two arithmetical processes. Here, for the first time, mass production was applied to arithmetic, and Babbage was seized by the idea that the labours of the unskilled computers could be taken over completely by machinery which would be quicker and more reliable. | ” |

—B. V. Bowden, Faster than thought, Pitman | ||

Babbage's machines were among the first mechanical computers, although they were not actually completed, largely because of funding problems and personality issues. He directed the building of some steam-powered machines that achieved some success, suggesting that calculations could be mechanised. Although Babbage's machines were mechanical and unwieldy, their basic architecture was very similar to a modern computer. The data and program memory were separated, operation was instruction-based, the control unit could make conditional jumps, and the machine had a separate I/O unit. For more than ten years he received government funding for his project, which amounted to £17,000.00, but eventually the Treasury lost confidence in Babbage.[25]

Difference engine

Main article: Difference engine

In Babbage's time, numerical tables were calculated by humans who were called 'computers', meaning "one who computes", much as a conductor is "one who conducts". At Cambridge, he saw the high error-rate of this human-driven process and started his life's work of trying to calculate the tables mechanically. He began in 1822 with what he called the difference engine, made to compute values of polynomial functions. Unlike similar efforts of the time, Babbage's difference engine was created to calculate a series of values automatically. By using the method of finite differences, it was possible to avoid the need for multiplication and division.

At the beginning of the 1820s, Babbage worked on a prototype of his first difference engine. Some parts of this prototype still survive in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford.[26] This prototype evolved into the "first difference engine." It remained unfinished and the completed fragment is located at the Science Museum in London. This first difference engine would have been composed of around 25,000 parts, weighed fifteen tons (13,600 kg), and been 8 ft (2.4 m) tall. Although Babbage received ample funding for the project, it was never completed. He later designed an improved version,"Difference Engine No. 2", which was not constructed until 1989–91, using Babbage's plans and 19th century manufacturing tolerances. It performed its first calculation at the London Science Museum returning results to 31 digits, far more than the average modern pocket calculator.